Zeanah Spaces Welcome First-Year Students and Researchers Alike

Engineering Vols stepping into the Zeanah Engineering Complex are welcomed into a transformative facility designed to immediately immerse them into the community of engineers. Multiple aspects of the college’s first-year programs and ongoing studies will benefit from new homes in the complex, with spaces that advance the state-of-the-art of education and research.

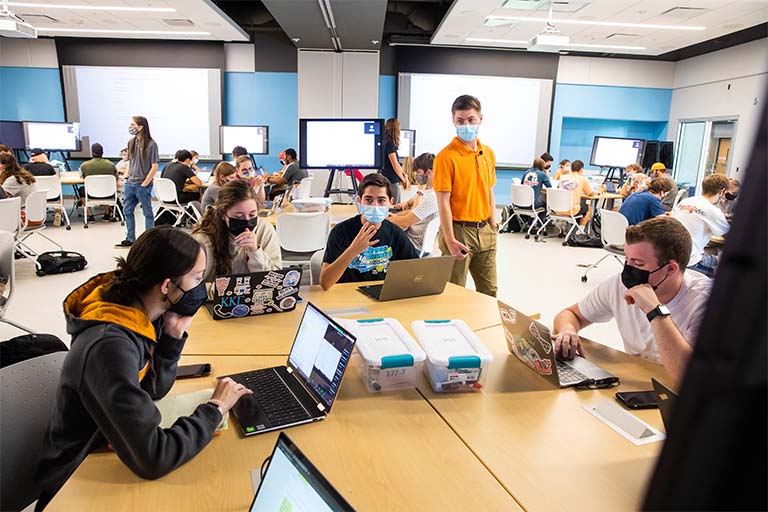

“Our first-year students will only experience a team-based classroom,” said Bill Dunne, associate dean for research and facilities. “They will take their first engineering classes without ever sitting in an auditorium.”

First-year students take part in either the Jerry E. Stoneking engage Engineering Fundamentals Program, which employs an innovative success-oriented educational approach that emphasizes problem solving through collaboration, or the Joseph C. and Judith E. Cook Grand Challenge Honors program, which offers a high level of intellectual challenges and broad educational experiences.

The new complex gives both programs a new home with room to thrive and grow.

“The new active-learning classrooms will allow for smaller class sizes, facilitating more personal interaction among students, faculty, and instructional staff,” said Interim Engineering Fundamentals Director Rachel Ellestad. “Movable walls will allow flexibility in how each class day is taught, with options for small class sizes for working days and large open classrooms for group lectures and discussions. With no defined front of the room, the focal point becomes the students and their work in the classroom.”

As they delve further into their experience, students will also explore the capabilities of the Min H. and Yu Fan Kao Innovation and Collaboration Studio. The studio works in tandem with classroom programs to provide students with the technology, tools, and knowledge to help them to turn inspiration into reality. Academic support specialists Tom Duong and Michael Allen know firsthand how the expanded studio allows them to share more of these resources.

“The beta test run of the original Kao Innovation and Collaboration Studio in Perkins Hall was fun,” said Duong. “But it has made us realize the desire for a bigger, better, and more updated maker space.”

“One thing that we have found through our time in Perkins is that if we get equipment, they will use it,” said Allen. “It’s kind of like in Field of Dreams: ‘If you build it, they will come.’”

Other areas of the complex are built with growth in mind for researchers at undergraduate and graduate levels. Flexible-use labs employ a variety of utilities, benching, and mechanical infrastructure, allowing for research in a wide range of engineering subdisciplines.

“The first thing about this is it is an expansion research lab and collaboration space,” said Dunne. “It is configured to house a variety of different kinds of research capabilities.”

The complex opened with 34 labs equipped with fume hoods and the ability to add 30 more as new research calls for them. The current roster includes 17 dry labs for possible chemical use, 10 wet labs with chemical use expected, and seven support labs that offer tools and equipment that enhance the work in the other labs.

New maker spaces and flex labs in the Zeanah Engineering Complex will foster innovation and accelerate and expand our ability to engage with industry partners through foundational research and senior design projects, while our first-year studies programs will empower students to engage with each other in meaningful collaborations from the moment they begin their academic journeys. By having both their initial research as first-year students and final projects as seniors in the building, it will truly serve as a ʻGateway to Engineering.’”

Spaces adjacent to the labs are designed to encourage collaborative moments, even when researchers are not actively engaged in their work.

“All kinds of different sorts of utility capabilities are met to be able to adapt and house different strategic initiatives,” said Dunne. “At the east end of the building on every floor, there is a kitchenette area and a small conference room. They’re quite informal and meant to create the opportunity for interactions and discussions and doing simple things like eating lunch or dinner.”

This inherent design for innovation and collaboration ensures that the complex will remain a launching point for our engineering Vols to light the way in their professional futures.

UT’s Gateway to Engineering

The inspiration for what is now the Zeanah Engineering Complex first began to come to life even before its most recent predecessor—the John D. Tickle Engineering Building—was fully completed.

Then dean Wayne Davis saw the opportunity to develop a new building that could not only serve as home to the college’s highly ranked nuclear engineering program, but also provide an opportunity to rethink how the campus community, alumni, and visitors thought of the Hill.

As a figurative gateway to engineering, the complex is a transformative facility designed to welcome and immerse students into the community of engineers—with spaces that advance state-of-the-art education and research, including first-year engineering programs, interactive and collaborative maker spaces, and administrative offices, in addition to nuclear engineering.

The John D. and Ann Tickle Atrium is the connective heart of the complex, with the Tennessee River meandering near one entrance while the Hill and the rest of the college’s departments are accessible from the other side.

The atrium was named in honor of the Tickles in recognition of their $7 million commitment, which started the process of securing campus and state funding for the complex. Their philanthropy—including a transformative gift that led to the college’s naming—has enabled the college to grow and meet the needs of contemporary engineering students.

Hallways spreading out from the atrium lead throughout the 228,000-square-foot complex to classrooms designed for engaged instruction and flexible-use research spaces, while alcoves on each floor offer opportunities for individual study and impromptu collaborative discussions.

The atrium is designed in such a way that the administrative offices, first-year program facilities, and innovation and collaboration studios can be secured on football game days while allowing work to continue in the nuclear engineering spaces.

A “Bumpy” Ride Advances Fusion

Fusion energy holds the promise of potentially limitless, carbon-free power and has been a major topic within nuclear engineering for decades.

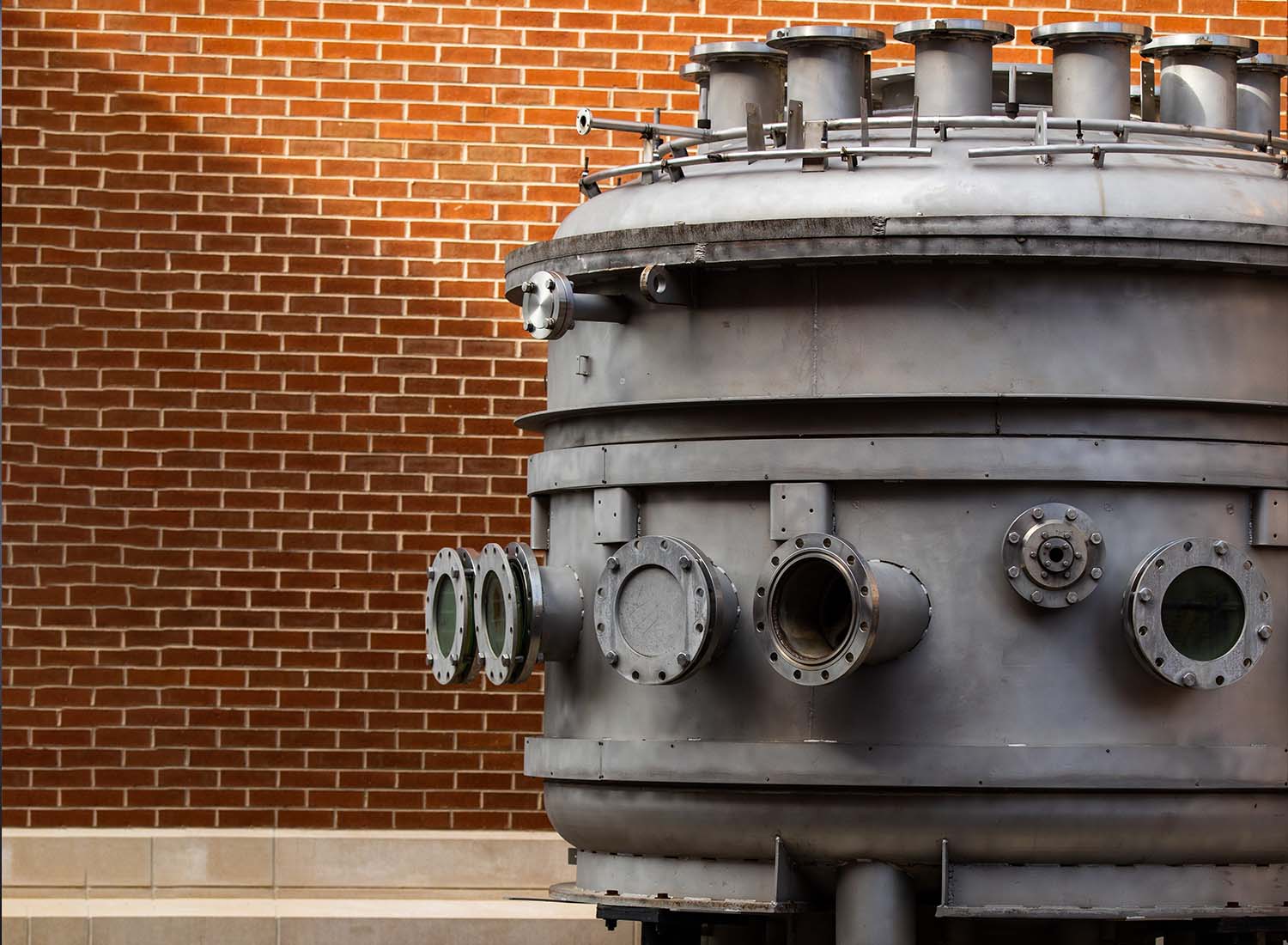

A giant machine located just outside the southeast corner of the new complex, known as a bumpy torus, is an early prototype of a fusion reactor. Its magnetic arrays help close the circular reactor chamber, or torus, which has been said to vaguely resemble a doughnut.

The “bumpy” part of the name is due to the behavioral nature of the plasma produced within—in particular, its tendency to pool and flow irregularly.

The concept was that the magnetic mirror arrays would help prevent leakage of particles that might otherwise be lost during operation due to small gaps in the machinery. The design also allowed for easier maintenance and replacement of parts within the reactor chamber.

While research on different models of bumpy torus—like fusion devices continued into the mid-1980s, including notable efforts at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, this particular device came to UT from NASA’s Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio.

Although other devices—tokamaks and, less frequently, stellarators—have been the focus of fusion efforts in recent decades, the bumpy torus still holds an important place in the quest to solve the fusion energy question.

The opening of the new complex and the consolidation of the department from several buildings into one provided the perfect opportunity to display it and to salute the work that paved the way for where we now stand.

-

A close look at one of the portals on the bumpy torus. -

The internal magnetic mirror chamber inside the bumpy torus where plasma was produced and contained.

Nuclear Fusion

Department Now Under One Roof

Nuclear engineering at UT has a long and prestigious history dating back to 1957. It holds the distinction of being the first program to be organized at the department level at a US college.

In the years since, the department has grown in size and reputation. Now the second biggest in the country, the department is annually ranked among the top institutions and features faculty and research that support national and international security.

What it hasn’t had is one centralized place to call home.

Until now.

Thanks to the new Zeanah Engineering Complex, the department can now house its faculty, classes, research, and staff in one building, ending decades of having spaces stretched across multiple buildings: the Pasqua Nuclear Engineering Building, the Science and Engineering Research Facility, Ferris Hall, and, most recently, the building that had previously housed the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

“It’s not just that being together will be nice, but rather it’s more about what the new space will allow us to accomplish,” said Department Head Wes Hines, who is also both a Chancellor’s Professor and Postelle Professor. “We will have three times as much space, with 23 new state-of-the-art laboratories dedicated to nuclear engineering, classrooms, offices, study areas, and lounges. This move will improve and enhance everything we do—not just now, but far into the future.”

And the growth isn’t just the number of spaces the department can claim. It’s also the quality of the labs within those spaces.

UCOR Fellow Jayson Hayward, the department’s associate head for graduate studies and research, will have expanded capabilities on his ground-floor lab. Its bunker-like walls and door are fit to secure the precious treasure inside: a linear accelerator that, in the hands of Hayward’s Rad IDEAS research group, could help with exploration of new techniques in gamma treatment of cancer and other medical conditions in addition to continuing his work in detecting potential radioactive threats.

Nuclear safety is at the forefront of Professor Howard Hall’s work, as well. As director of the Institute for Nuclear Security, Hall is responsible for helping monitor the status of nuclear stockpiles—in particular, determining whether countries are living up to their end of the deal in regard to nuclear treaties. His new lab space will allow him to further expand his work into nonproliferation, nuclear forensics, and radio chemistry.

It’s not just that being together will be nice, but rather it’s more about what the new space will allow us to accomplish…This move will improve and enhance everything we do, not just now, but far into the future.”

Eventually, the building will also house a fast neutron source, allowing students and researchers to design the reactors of the future in a safe way using a variety of variables.

“No one else in the country has a fast flux facility like that,” said Hines. “It will help us prepare our graduates for work in a variety of nuclear-related fields in ways that other universities can’t, while at the same time presenting faculty with an avenue to conduct novel research. We’re excited about the possibilities, to say the least.”

The move into the new building won’t happen overnight—priority was given to getting student spaces and classrooms ready ahead of any movement of lab spaces, for example—but it will help the department show off its capabilities in ways that were previously constrained, and to do so across the board in a cohesive way.

Together. At last.