By Izzie Gall. Photography by Randall Brown.

When looking for ways to reduce their carbon footprint, most people think of first of their car, not their house. Surprisingly, however, buildings make up one of the largest energy-consuming sectors of the US economy, accounting for 39 percent of the country’s total energy use.

“Heating and cooling are among the most energy-intensive parts of building operations,” said Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Nick Zhou, who leads UT’s Sustainable and Adaptive Built Environment Group in researching sustainable, energy-efficient building materials and systems.

On top of the baseline cost of indoor temperature control, air can leak out through poorly sealed windows, crooked doors, and even cracks in the roof and exterior walls. Around 30 percent of the energy funneled into buildings—worth about $150 billion every year—is wasted.

Most of that loss is borne by low-income communities, where homes tend to be old, poorly insulated, and equipped with obsolete air conditioning systems.

“This inferior environment leads to high electric bills and uncomfortable living conditions,” said Zhou. “Poorly insulated houses not only cause significant energy burdens to lower income households, they create a lot of the environmental justice issues we see nationwide.”

Some government programs help cover the costs of energy-saving home retrofits like upgrading interior insulation, but they may not include lodging for residents displaced during the extended renovation process. As a result, many households that qualify for the upgrades may decline them.

“The trends of climate change are increasing the need for comfortable, well-insulated homes, further aggravating these problems,” Zhou said. “We need a technology that can retrofit a building quickly, with no or minimal disturbance to the occupants, and we need it soon.”

In September, Zhou secured $1.5 million to develop an innovative technique that will insulate and seal a home’s exterior in just a few days. The new technology, called MonoInsu, was funded as part of a $46 million research boost from the US Department of Energy’s Building Technology Office to reduce energy consumption by buildings.

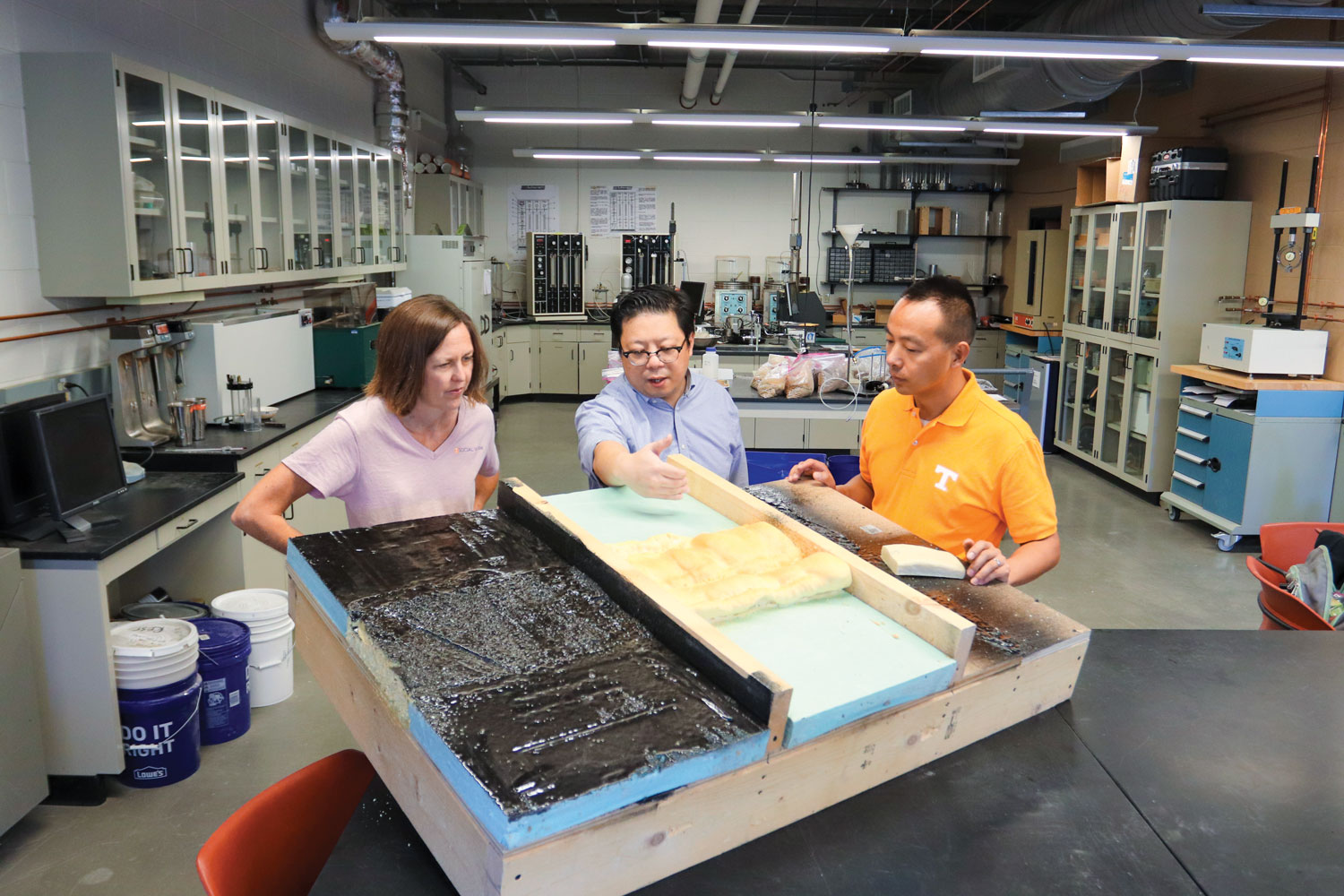

Zhou’s team is partnering with Oak Ridge National Laboratory to test and evaluate MonoInsu’s performance. They begin by applying two inches of insulation with a patent-pending process that benefits from both the rapid coverage of panel insulation and the precision of spray foam. The insulation is then sprayed with an innovative polymer that creates a seamless protective shell around the building.

Poorly insulated houses not only cause significant energy burdens to lower income households, they create a lot of the environmental justice issues we see nationwide.”

To further reduce the environmental impact of the retrofitted homes, Assistant Professor Mi Li of UT’s Herbert College of Agriculture is developing effective insulation from a renewable plant material called lignin. The research team will collaborate with representatives from three major insulation trade organizations to ensure that the new foams are of high quality and can be quickly adopted by the national building industry.

The MonoInsu system is effective, quick, and inexpensive— costing less than five dollars a square foot—but it has one final hurdle to cross.

“This solution can be as effective as you can imagine,” Zhou said, “but if it’s unsightly, nobody will want to use it.”

MonoInsu’s makeover starts with Associate Professor Courtney Cronley of UT’s College of Social Work, who studies the intersection of housing and community well-being. Cronley will collaborate with architecture students to examine socioeconomic factors affecting acceptance of MonoInsu, such as interest in increasing sustainability, trust in new technology, and the impact of potential motivators like tax breaks—as well as people’s preferences for different exterior colors and textures.

“This is a unique and important aspect of MonoInsu,” Zhou said. “We’re interfacing with the public at the very beginning to make sure that the technology we are developing will get accepted and used.”

The team has already had a major aesthetic success, achieving an adobe texture for the polymer spray without sacrificing its functionality.

Promising variations of MonoInsu will be piloted in underserved communities in Knox County based on recommendations from Knoxville’s Community Development Corporation before being advertised to homeowners, landlords, and building contractors around the nation.

“MonoInsu addresses energy justice through both technology and sociology,” said Zhou. “We can reduce energy bills, increase thermal comfort, and improve aesthetics for low-income communities in one step.”