Steve Abel and Andy Sarles serve in different departments—Abel is an associate professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and Sarles is an associate professor and James Conklin Fellow in the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace and Biomedical Engineering—but their offices share the same hallway in the Nathan W. Dougherty Engineering Building. And they have used that proximity to their advantage.

What started as a casual exchange of ideas grew into a collaboration that earned a small internal seed grant. Their work continues now as a new three-year project funded by the National Science Foundation.

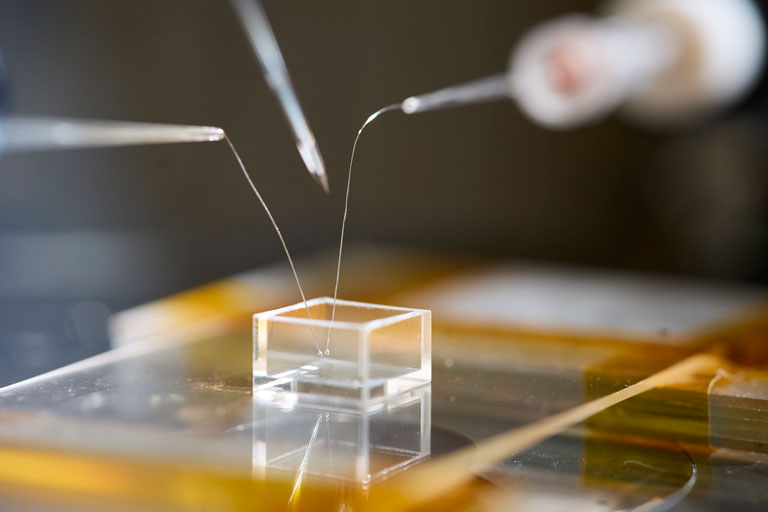

“This project demonstrates the vibrant interdisciplinary research environment cultivated at UT and within the Tickle College of Engineering,” Sarles said. “Through this project, we aim to answer focused questions about how flexible nanoscale particles interact with flexible biomembranes. Nanomaterials have so much promise for benefiting cellular function and health, but so far existing studies have focused on rigid nanoparticles.”

The two principal investigators visualize the fundamental science of the project as an early stepping stone toward designing flexible nanoparticles that function in a wide variety of applications, such as measuring specific properties of cells, reshaping membranes, and even redistributing proteins or other molecules within the cell membrane.

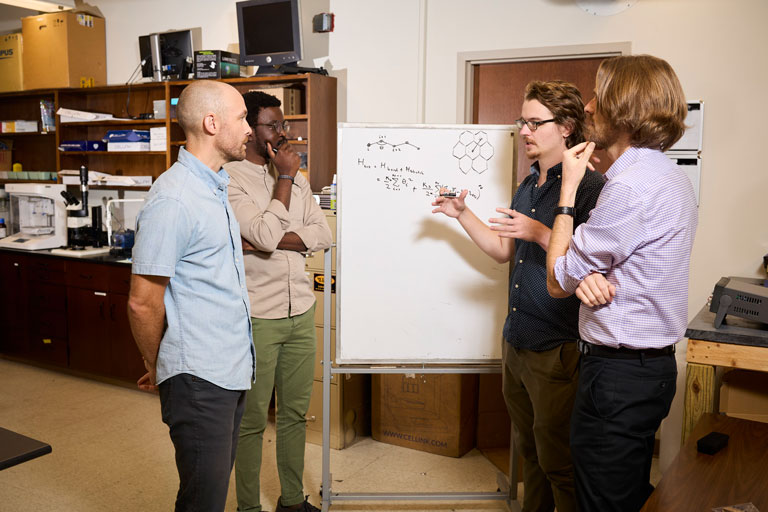

“The goal for both of us is to build the fundamental understanding of the interface between biology and materials,” Abel said. “It will hopefully enable engineering of biological membrane systems. But we come at it from different complementary perspectives.”

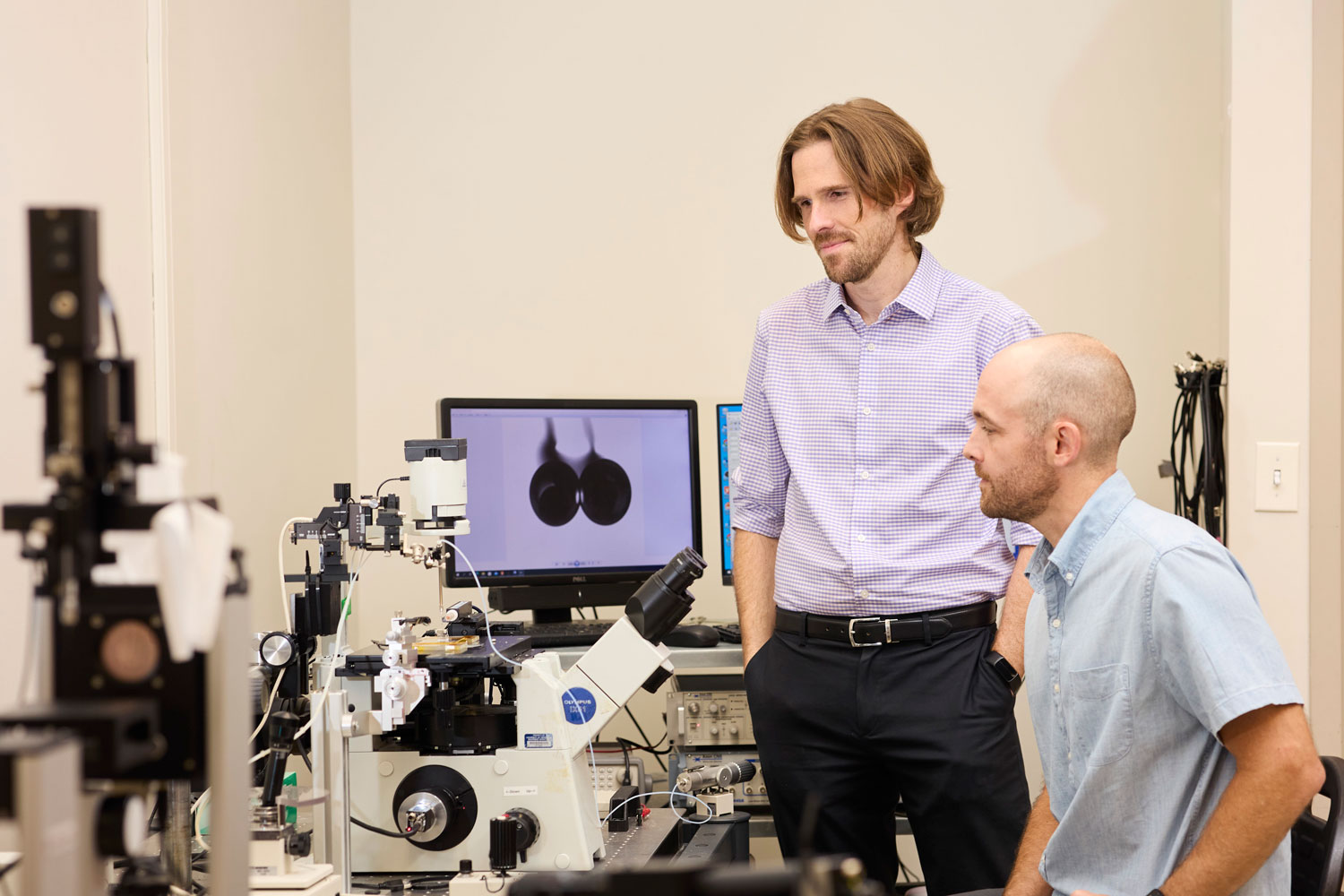

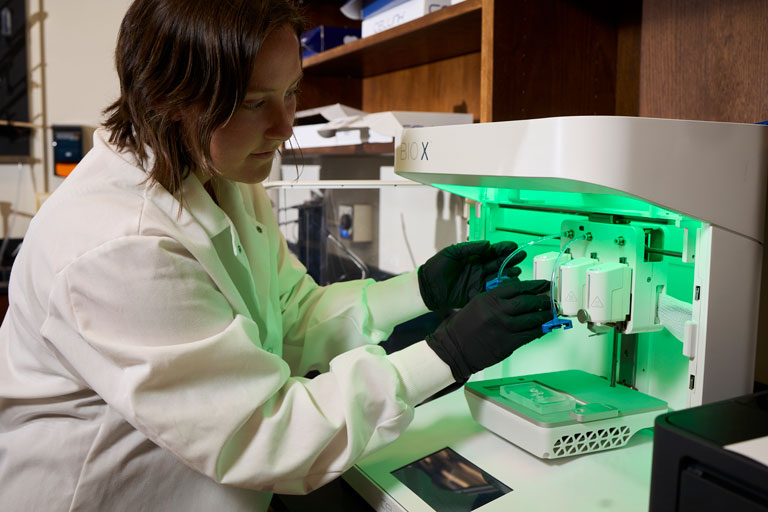

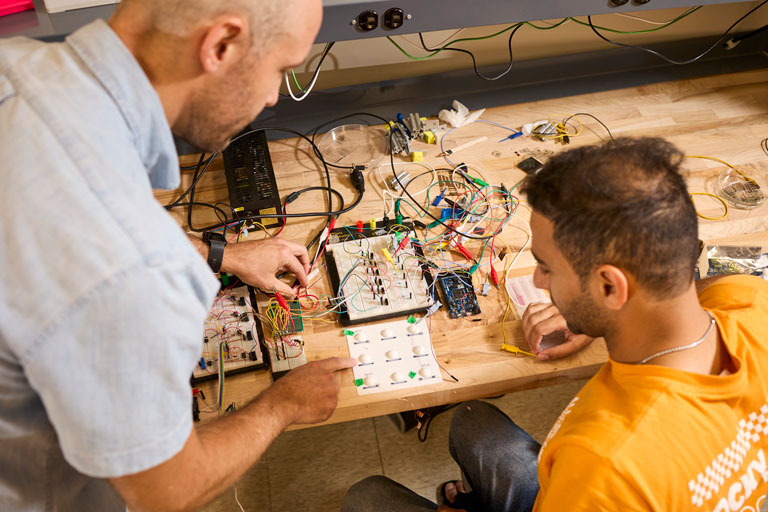

Abel’s research group uses mathematical modeling and computer simulations to understand biological environments, like membranes. Sarles’s group, on the other hand, uses experimental techniques that bring together biology and engineering.

Each professor’s research group will be able to see more together than they could alone.

“The nanoparticles are incredibly small, so experimentally it’s difficult to see how a single one interacts with a membrane,” Sarles said. “That’s where Steve’s computational methods are such a complement.”

Abel explained what his group brings to the project: “My group’s simulations give us much more detailed molecular insights. But here’s our technical challenge: we can’t simulate a whole cell. The particles and cells might be tiny, but they’re composed of so many atoms that modeling an entire cell at this scale would require tremendous supercomputing resources.

By using experimental data, Abel’s group will be able to build simplified models that focus on a small number of nanoparticles interacting with a particular patch of a cell membrane.

“This is a two-way street,” Abel said. “Experiments need insights from simulations, and experiments help us build and refine our simulation models.”

The two agree that the collaboration is as exciting as the science itself.

Having both experimental and computational approaches is going to push us in new directions. It’s going to open up new avenues for research beyond this project. It just makes sense for the science itself to have investigators with complementary skills and different backgrounds.”

It also enables more students to learn about the intersections between engineering disciplines, materials science, and biology.

“This project is important from a training perspective as we bring in students from mechanical and chemical engineering to collaborate and bridge the gap between experiments and computations,” Abel said.

The NSF funding will support two full-time doctoral students, several undergraduate students, and outreach activities to teach many others.

Sarles points out how this project fits into the larger fabric of meaningful interdisciplinary research in progress at UT.

“There’s a community of scholars at UT that work on membrane science and cellular interfaces in different disciplines,” he said. “Our work adds to the momentum of collaborating across departments.”

And that momentum travels a two-way street.